Back قياس ضوئي فلكي Arabic Fotometría AST Fotometriya (astronomiya) Azerbaijani Fotometria Catalan Astrofotometrie German Φωτομετρία Greek Fotometrio (astronomio) Esperanto Fotometría Spanish Fotomeetria (astronoomia) Estonian Fotometria Basque

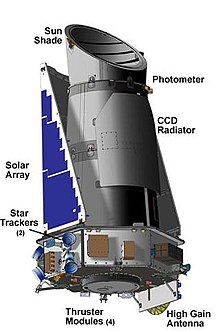

In astronomy, photometry, from Greek photo- ("light") and -metry ("measure"), is a technique used in astronomy that is concerned with measuring the flux or intensity of light radiated by astronomical objects.[1] This light is measured through a telescope using a photometer, often made using electronic devices such as a CCD photometer or a photoelectric photometer that converts light into an electric current by the photoelectric effect. When calibrated against standard stars (or other light sources) of known intensity and colour, photometers can measure the brightness or apparent magnitude of celestial objects.

The methods used to perform photometry depend on the wavelength region under study. At its most basic, photometry is conducted by gathering light and passing it through specialized photometric optical bandpass filters, and then capturing and recording the light energy with a photosensitive instrument. Standard sets of passbands (called a photometric system) are defined to allow accurate comparison of observations.[2] A more advanced technique is spectrophotometry that is measured with a spectrophotometer and observes both the amount of radiation and its detailed spectral distribution.[3]

Photometry is also used in the observation of variable stars,[4] by various techniques such as, differential photometry that simultaneously measures the brightness of a target object and nearby stars in the starfield[5] or relative photometry by comparing the brightness of the target object to stars with known fixed magnitudes.[6] Using multiple bandpass filters with relative photometry is termed absolute photometry. A plot of magnitude against time produces a light curve, yielding considerable information about the physical process causing the brightness changes.[7] Precision photoelectric photometers can measure starlight around 0.001 magnitude.[8]

The technique of surface photometry can also be used with extended objects like planets, comets, nebulae or galaxies that measures the apparent magnitude in terms of magnitudes per square arcsecond.[9] Knowing the area of the object and the average intensity of light across the astronomical object determines the surface brightness in terms of magnitudes per square arcsecond, while integrating the total light of the extended object can then calculate brightness in terms of its total magnitude, energy output or luminosity per unit surface area.

- ^ Casagrande, Luca; VandenBerg, Don A (2014). "Synthetic stellar photometry - General considerations and new transformations for broad-band systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 444 (1). Oxford University Press: 392–419. arXiv:1407.6095. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.444..392C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1476.

- ^ Brian D. Warner (20 June 2016). A Practical Guide to Lightcurve Photometry and Analysis. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-32750-1.

- ^ C.R. Kitchin (1 January 1995). Optical Astronomical Spectroscopy. CRC Press. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-1-4200-5069-1.

- ^ Miles, R. (2007). "A light history of photometry: from Hipparchus to the Hubble Space Telescope". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 117: 178–186. Bibcode:2007JBAA..117..172M.

- ^ Kern, J.~R.; Bookmyer, B.~B. (1986). "Differential photometry of HDE 310376, a rapid variable star". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 98: 1336–1341. Bibcode:1986PASP...98.1336K. doi:10.1086/131940.

- ^ Husárik, M. (2012). "Relative photometry of the possible main-belt comet (596) Scheila after an outburst". Contributions of the Astronomical Observatory Skalnaté Pleso. 42 (1): 15–21. Bibcode:2012CoSka..42...15H.

- ^ North, G.; James, N. (21 August 2014). Observing Variable Stars, Novae and Supernovae. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-63612-5.

- ^ "Overview: Photoelectric photometer". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ Palei, A.B. (August 1968). "Integrating Photometers". Soviet Astronomy. 12: 164. Bibcode:1968SvA....12..164P.